Scientists recognize seven living species of sea turtles, which are grouped into six genera. Each sea turtle has both a scientific name and a common name. The scientific name identifies the genus and species, and the common name typically describes some characteristic of the turtle’s body.

Different species of sea turtles like to eat different kinds of food. Sea turtles have mouths and jaws that are specially formed to help them eat the foods they like. And each species of sea turtle eats, sleeps, mates and swims in distinctly different areas. Sometimes their habitats overlap, but for the most part they each have different preferences.

Click on each turtle’s common name to learn more about that species and view a map of their world-wide distribution and nesting sites.

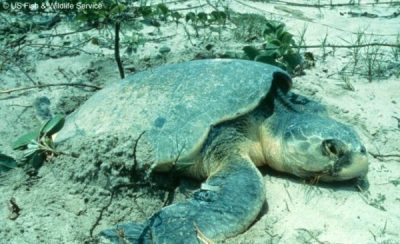

Of all the sea turtles that nest in the United States, the loggerhead is the one seen most often. The loggerhead was listed in the United States under the Endangered Species Act as threatened in 1978, and is the only sea turtle species not listed as endangered. Loggerhead populations in Honduras, Mexico, Colombia, Israel, Turkey, Bahamas, Cuba, Greece, Japan, and Panama have been declining. The majority of loggerhead nesting is concentrated in two main areas of the world — at Masirah Island, Oman, in the middle east and on the coast of the southeastern United States. The Masirah Island’s annual nesting population is about 30,000 females, while up to 25,000 loggerheads nest in the southeast U.S. each year. The majority of nesting in the southeast U.S. takes place on Florida’s Atlantic coast between the inlet at Cape Canaveral and the Sebastian Inlet, especially within the Archie Carr National Wildlife Refuge.

Green turtles are an endangered species around the world, but they still nest in increasing numbers on the east coast of Florida. The green sea turtle was listed in the United States under the Endangered Species Act as endangered in 1978. The largest nesting site in the Western Hemisphere is at Tortuguero, Costa Rica, where STC has been running a research program since 1959. While the nesting population may be stable in Suriname, and increasing in Tortuguero, there is insufficient information from other nesting sites to determine a species trend worldwide.

The leatherback is the champion of sea turtles: It grows the largest, dives the deepest, and travels the farthest of all sea turtles. The leatherback was listed in the United States under the Endangered Species Act as endangered in 1970. Populations have declined in Mexico, Costa Rica, Malaysia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Trinidad, Tobago, and Papua New Guniea. Leatherbacks are seriously declining at all major nesting beaches throughout the Pacific. The decline is dramatic along the Pacific coasts of Mexico and Costa Rica and coastal Malaysia. Nesting along the Pacific coast of Mexico declined at an annual rate of 22% over the last 12 years, and the Malaysian population represents 1% of the levels recorded in the 1950s. In contrast, there has been a recent increase in leatherback nesting on the central and south eastern coast of Florida.

The hawksbill turtle’s status in the United States has not changed since it was listed under the Endangered Species Act as endangered in 1970. It is a solitary nester, and thus, population trends or estimates are difficult to determine. The decline of nesting populations is accepted by most researchers. In 1983, the only known apparently stable populations were in Yemen, northeastern Australia, the Red Sea, and Oman. Although they are found in U.S. waters, they rarely nest in North America. While hawksbills nest on beaches throughout the Caribbean, they are no longer found anywhere in large numbers.

Kemp’s ridley is the most endangered of all sea turtles and was listed in the United States under the Endangered Species Act as endangered throughout its range in 1970. The only major breeding site of the Kemp’s ridley is on a small strip of beach at Rancho Nuevo, Mexico. Kemp’s ridleys nest in mass synchronized nestings called arribadas (Spanish for “arrival”). The arribada of Kemp’s ridleys occurs at regular intervals between April and June. In 1942, a Mexican architect filmed an estimated 42,000 ridleys nesting at Rancho Nuevo in one day. During 1995, only 1,429 ridley nests were laid at Rancho Nuevo. Recent good news is that the nesting at Rancho Nuevo seems to be increasing with over 7,100 nests recorded in 2004! The increase can be attributed to two primary factors: full protection of nesting females and their nests in Mexico, and the requirement to use turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawls both in the U.S. and Mexican waters.

The western North Atlantic (Surinam and adjacent areas) nesting population has declined more than 80 percent since 1967. Declines are also documented for Playa Nancite, Costa Rica, however other nesting populations along the Pacific coast of Mexico and Costa Rica appear stable or increasing. In the Indian Ocean, Gahirmatha located in the Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, India, supports perhaps the largest nesting population with an average of 398,000 females nesting in a given year. This population continues to be threatened by nearshore trawl fisheries. It is very oceanic in the Eastern Pacific and probably elsewhere too. Large arribadas of olive ridleys still occur in Pacific Costa Rica, primarily at Nancite and Ostional and Pacific Mexico at La Escobilla, Oaxaca.

Australian flatbacks are medium size turtles that inhabit coastal coral reef and grassy shallows and is only found in the northern coastal area of Australia and the Gulf of Papua, New Guinea. The shell is very smooth and waxy, and can be easily damaged.